Welcome to the world of the James Bond films novelizations.

The trend for turning films or TV series into novels started during the second half of the 20th century. It was the era prior to the home video boom and a way to experience the film at home. This technique is still continued in many franchises for those who want to go beyond the cinematic experience of a motion picture and learn a little more of the background and thoughts of each of the characters in the story.

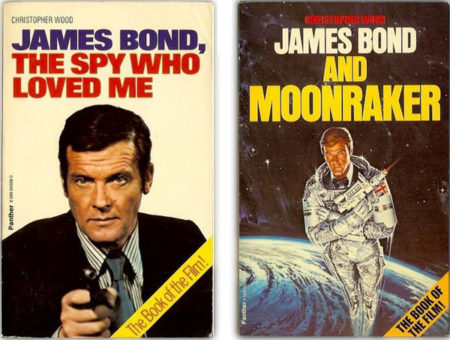

Even when agent 007 was already a popular icon in literature by 1977, when The Spy Who Loved Me was released, screenwriter Christopher Wood was commissioned to adapt his script for the tenth James Bond cinematic adventure into a novel. This was a time when the literary Bond was in limbo after the passing of Ian Fleming. Bond was the protagonist of Kingsley Amis’ Colonel Sun in 1968 and the subject an “authorized” biography by John Pearson in 1973, but that was all.

Ian Fleming wasn’t pleased with the source novel –written from the point of view of a woman in danger saved by his creation– and stipulated that if a cinematic adaptation was made of it the producers should only use the title.

Scribes like Richard Maibaum, Tom Mankiewicz and Anthony Burgess offered different scripts until Maibaum’s draft was accepted. Christopher Wood was then brought to contribute on the movie after working for director Lewis Gilbert in Seven nights in Japan.

Of all seven Bond novelizations written to date by three different authors, The Spy Who Loved Me is the one that differs most of the tie-in movie.

Also titled James Bond, The Spy Who Loved Me to avoid confusion with the 1962 Ian Fleming novel, the book takes a lot of influence from Bond’s creator. It is the literary James Bond –not Roger Moore’s 007–who stars in the story. Wood makes sure to use the classic description of 007 resembling musican Hoagy Carmichael (tall, slim, blue-grey eyed, with a comma of his black hair falling on his forehead) and even adds a torture scene that is almost copied from 1953’s Casino Royale, with electric shocks in place of the infamous carpet beater. Wood himself admitted to have read the Fleming books trying to adapt his style.

Unlike the action-hero of the movie, in this version James Bond (his zodiac sign is Scorpio, by the way) bleeds, faints and almost vomits when he discovers the corpse of Max Kalba, brutally bitten in the neck by Jaws. Most of the humorous lines of the film are omitted, even when the action scenes are similar.

The characters are thoroughly described as Fleming did, particularly the villain Sigmund Stromberg (Karl in the movie), whose background is expanded. We know how he made his fortune, how he plotted the death of his parents and how big is his ambition of a new world beneath the sea. We also get more data on many characters that in the movie seemed to come from nowhere like the cabin girl (a woman Bond met in a Casino in France) and Jaws (a former basketball player who was captured by the police and had his teeth broken with clubs).

One of the most interesting differences is that the KGB whom the British Secret Service allies in the movie is replaced here with SMERSH, the assassination branch of the Soviet Intelligence whom 007 confronted in the early Fleming novels.

The mild General Gogol that will appear in the film is put completely aside and the unpleasant General Nitkin, who was mentioned in From Russia With Love (1957), is here in charge of SMERSH. The appearance of Nitkin complicates the relationship between Bond and Anya Amasova even more as he is the one who sends her a message revealing that 007 killed her former lover Sergei Borzov on a mission in Chamonix (in the movie it is Berngarten, Austria).

The new leader of SMERSH is highly uncooperative with the British unlike his big screen counterpart, bringing Anya (a deathly female agent) to the mission in order to have James Bond killed after the collaboration between the two powers comes to an end.

In 1979, Moonraker also received the novelization treatment from Christopher Wood, this time the sole writer of the movie. Retitled James Bond and Moonraker to avoid confusion with the 1955 Ian Fleming novel, the book is considerably closer to the film than its predecessor.

It begins very much like the movie, with the hijacking of the Moonraker shuttle onboard a 747 travelling from America to the United Kingdom. Wood explores the lives of the pilots carrying on the transportation of the space craft before their ultimate death as the shuttle ignites causing the plane to go up in smoke.

Once again, is very much clear that the James Bond in this book is the one written by Ian Fleming and not Roger Moore, who starred in the film. Upon chapter two we are given an insight on his dangerous lifestyle as described by Fleming on many of his novels, like his addiction to nicotine and alcohol.

Much like in the previous novelization, Bond will bleed and hurt way more than the cinematic version: he even gets his arse burned while escaping from the shuttle fire in one of the villain’s deathtraps.

Hugo Drax, the villain in the story, shares the same name with the mastermind from Ian Fleming’s thriller published 1955. Nevertheless Wood’s version of this villain for the novelization adopts the likeness of the villain as conceived by Fleming: with red hair and an unsuccessful attempt of a plastic surgery over his right temple and cheek. The villain’s ties to the Nazi Germany as reflected by Fleming also come back with a hint over the pages of Wood’s book.

What is more interesting is that in the novel an explanation is given an explanation on why Drax attempts to create a master race in space: he’s worried about the overpopulation of a “decadent” human race leading to a a significant decrease of livestock and nature.

Also, there are quite a few moments apparently envisioned in early drafts that Wood used for James Bond and Moonraker, one of them is the way 007 gets on an astronaut’s suit and leaves the antagonist’s space station to outer space to manually deactivate the laser cannon threatening the American shuttle, while he avoids his own allies trying to shoot at him as he’s wearing a suit with the enemy insignia. Some other moments discarded for the film have a zero gravity lovemaking scene of a couple from Drax’s “master race”, a restaurant with precooked food inside the station, and Bond escaping from Jaws using Holly Goodhead’s flamethrowing perfume atop the cable car in Rio de Janeiro.

Drax’s pilot and Corrinne Dufour maintains her original name, Trudi Parker, and is described as a Californian blonde instead of the French brunette played by Corinne Clery. Her demise is equally fatal as in the movie, only this time Bond is told of her death by Holly in Venice, making his desire to run down Hugo Drax even more personal.

While the humour is considerably reduced in comparison to the movie, a funny note happens at the very end when we see Frederick Gray’s political ambitions. Knowing that M’s and Bond’s identity can’t be disclosed, the Minister of Defence knows he’ll get the credit of the success on the space mission against Drax. His joy is, of course, interrupted when 007 and Dr Goodhead are caught lovemaking on camera transmission.

All in all, the novelizations of The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker are an entertaining read. The first one excels by providing the reader a more dramatic take on the film that abounded in escapism and humoristic moments, the second is tighter to the movie but it also offers many interesting twists. As a first time for something in the Bond franchise, these two books are unique because Christopher Wood bet on morphing a cinematic James Bond story with a Fleming-esque thriller.

Part II of this Bond novelization essay will cover the book adaptations of two 007 films, Licence to Kill and GoldenEye, by John Gardner.

Nicolás Suszczyk is editor of The GoldenEye Dossier and Bond en Argentina.

May 2nd, 2017 at 22:08

“Ian Fleming wasn’t pleased with the source novel –written from the point of view of a woman in danger saved by his creation– ”

Correct me if I’m wrong, but wasn’t the source of the source novel Fleming himself?

May 3rd, 2017 at 11:16

Yes he was. The author is differentiating between the original novel (the source) and the novelization.