Just a few days prior to the publication of Thunderball Ian Fleming received the shock news that Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham sought an injunction preventing publication.

McClory had read an advance copy of the novel in March 1961 and was infuriated to see that Fleming had based the story on a screenplay written by him, Whittingham and Fleming, who had used the material with neither acknowledgement nor permission.

The court hearing took place on March 24th, just a few days before publication on March 27th, but while the judge ruled that the pair had a case, he ruled that publication should go ahead.

The whole sorry story resulted in a string of complications after Fleming conceded the case when it came to court in November 1963. Fleming himself suffered his first heart attack likely due to stress, while the result of the case complicated the rights to the film series that Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli had believed they owned, with the exception of Casino Royale, in its entirety. On numerous occasions in the years that followed Eon Productions/MGM was forced to fight their corner in court until finally reaching a settlement with Sony in 1999 that saw them awarded the rights to Casino Royale.

Ian Fleming’s big screen ambitions

Fleming had long held the ambition of putting his hero on the big screen but his initial efforts proved fruitless. Eventually he teamed up with friend Ivar Bryce to make a James bond film from an original screenplay.

Also brought into the project was Kevin McClory, who had worked as assistant director to John Huston, and associate producer and second unit director on Mike Todd’s Around The World In 80 Days and later directed a film for Bryce’s Xanadu Productions called The Boy And The Bridge.

McClory saw the big screen potential of James Bond and was ambitious and in order to further the screen treatment he brought in screenwriter Jack Whittingham.

When the project collapsed, Fleming used the script as the basis of Thunderball; while taken at face value that might seem like he was acting in bad faith, he had previously reused material developed for aborted television projects and no doubt believed he could do the same with Thunderball.

The result of the trial not only had implications for Fleming’s health and reputation; Eon’s first 007 film was originally to have been Thunderball, but following the court decision they instead plumped for Dr No.

007 film rights held by 3 parties

Furthermore, following the trial, the film rights were held by three separate parties; the bulk of the rights were owned by Eon Productions, Thunderball was owned by Kevin McClory (Jack Whittingham dropped out of the court action due to the costs involved) and Casino Royale was owned by Gregory Ratoff, then Charles K Feldman (who produced the 1967 spoof) and then Sony.

Eon made a smart move by bringing in McClory to make Thunderball as part of their film series. In doing so they prevented a rival series of Bond movies getting off the ground just as 007 was becoming a global phenomenon, although that is exactly what McClory later tried to do, although in the end he was limited to a single remake of Thunderball with Never Say Never Again (1983) staring Sean Connery.

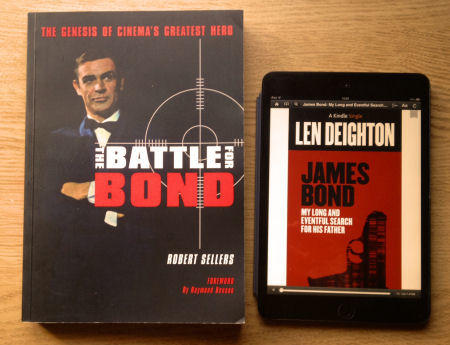

Recommended reading

Two books that are worthwhile reading about the background to Thunderball and all the characters involved in the case are The Battle For Bond by Robert Sellers, first published in 2007, and James Bond: My Long and Eventful Search for His Father by Len Deighton, author of The Ipcress File.

Sellers’ book covers in whole story in detail and as well as covering Never Say Never Again and McClory’s subsequent attempts to bring his own 007 series to television and later to remake Thunderball yet again with Sony under the title Warhead. The resulting lawsuit ended in a settlement that saw the rights to Casino Royale finally being awarded to MGM/Eon Productions by Sony, paving the way for the hugely successful reboot with Daniel Craig in 2006.

McClory’s own lawsuit claiming fees from Eon for the entire series was thrown out by a US court in 2000 because he had delayed legal action too long, a decision upheld by the appeal court the following year.

Get hold of a first edition copy from Ebay or Abebooks if you can as it includes some correspondence with Ian Fleming that was later removed due to legal issues.

Len Deighton’s title is only available for Kindle and is interesting, as he knew both Ian Fleming and Kevin McClory. Indeed, Deighton wrote an early draft of the script that eventually became Never Say Never Again and fleshes out McClory’s good side as well as acknowledging his flaws.

Both books are available from Amazon, below:

The Battle for Bond (2007, Robert Sellers)

James Bond: My Long and Eventful Search for His Father (2013, Len Deighton)