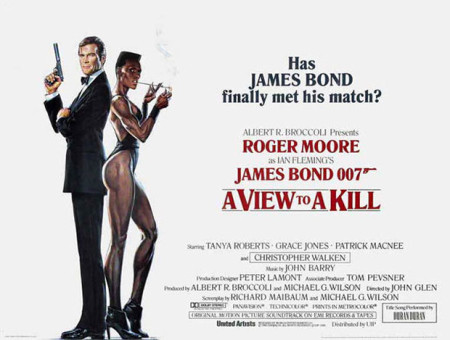

Its high-speed vehicle of choice is an airship. Its breaks between the action “hits” run a little longer than we’re generally accustomed. Its woman of choice is decidedly out of her depth in this espionage world. So, it would seem, is our seasoned James Bond, as the crazed villain of the piece helpfully reminds us. “It” is A View to a Kill – often maligned for the above reasons (and more), but a film that extends the James Bond mythos in particularly interesting and effective ways.

It takes the template of a Roger Moore romp and sneakily subverts it with a nihilistic edge. This is reinforced most evidently when the film is reaching its conclusion: a shot of collapsed structures and lifeless bodies in a flooded mine, for instance, is immediately followed by the gag of a fisherman wondering where all the water has gone. He could equally be wondering how sobering material has seeped its way into the escapist frivolities.

This quality is flagged as early as during the film’s pre-credits sequence, when the not-always-appreciated audio joke of California Girls is soon followed by unsettling shots of panicked helicopter pilots, lost in the reddish wake of a flare. Even the central joke of the police chase – the cops trapped on a rising drawbridge – is soon undercut by the pride-deflating degree of the men’s panic.

Some might suggest that nihilism be coupled with a more serious tone. I think we’ve recently had a Bond film that embraced just that: 2008’s Quantum of Solace, another controversial piece, but for markedly different reasons. Personally, I’ll go with the film that balances the dark and the playful with consummate flair.

The corporate bad guy of A View to a Kill, Christopher Walken’s Max Zorin, has a particular brand of domination in mind; namely, domination for domination’s sake. No dreams of remaking the world in any idealised form. For some, this “void” is a negative in the Zorin character. It’s also an integral part of what makes the character unsettling. Moore’s Bond, so often suave in the give-and-take with past villains, can only express repulsion. It’s an excellent switch on expectations.

Zorin’s horse racing shenanigans in the film’s first half are – at face value – barely related to the central plot, but it’s terrific to observe on repeated viewings how innocuously and subtly references to the chief conspiracy are threaded throughout these diversions. Furthermore, this minor conspiracy adroitly sets up themes of cold, calculated “competitive edge”– and the disposability of the horses (not shown, but certainly suggested) we will soon see extends to the villain’s workforce as well. Bond, meanwhile, “nonchalantly” wanders Zorin’s estate in engaging style, not unlike Lazenby’s Bond wandering Piz Gloria in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

On the topic of subtle effects, A View to a Kill is clearly an action-adventure film that recognises how effective the use of quiet can be in an escapist context. Quiet? Have the filmmakers lost their action-focussed faculties? Not really. Rather, they simply recognise that engagement can be drawn from avenues other than a high volume, insistent movement and editorial bluster. The Dolby Stereo action is still there, but the marked contrasts in the use of sound play on expectation. The silence brings with it a sense of foreboding – a quality that can energise as much as bringing in another action set piece.

What about the matter of Grace Jones’ physically menacing May Day “turning good”? In his supremely entertaining and informative The Man with the Golden Touch, author Sinclair McKay quipped that we were witnessing the fastest moral turnaround in cinematic history. Although, really, no turnaround has occurred. May Day’s assistance in preventing the flooding of Silicon Valley could have been crushingly corny, but the moment it becomes apparent her actions have not been guided by compassion for Silicon Valley residents (rather, by rage at a lover’s betrayal) delivers a memorable frisson.

Tanya Roberts’ Stacey Sutton, by contrast, is no toughie – and she hasn’t been written with any particular imagination or real shading. But does she require the shading? Tonally, she’s right on the money: providing a counterpoint – a principled, kind and timid “glamour puss” Bond Girl – to two glamorously amoral and assured central villains.

Not once does Moore’s Bond slip into condescension as he assists Stacey. He plays the game with May Day and Fiona Fullerton’s Pola Ivanova, but has the moral wherewithal to drop the act with the woman evidently in need. It’s a terrific contrast; hardly overstated, but there to be discovered and appreciated.

Then there’s the sumptuous location photography, a gorgeous score, an airship sailing over San Francisco Bay. Surely we can say it’s a classic of its type. Surely? In any case, happy 30th A View to a Kill.

Andrew McNess is the author of A Close Look at ‘A View to a Kill’. His other Bond-related writings can be found at A View on Bond.

Andrew’s book is available online in various formats from the following links:

June 2nd, 2015 at 18:37

A though-provoking piece and I’m inclined to agree with a lot of it. My “least favourite” Bond film has changed over time and it has been this one before but not currently.

I enjoy the inclusion of Patrick Macnee (always excellent as John Steed) as Tibet.

I like some of the score which I think reworks the main theme rather well (I like the music on the wedding barge).

Having recently visited San Francisco you can imagine my excitement as I was walking down the street to visit one of the piers to find myself face to face with the imposing drawbridge of the 3rd street bridge.

June 9th, 2015 at 23:59

Moore was the worst of the Bonds. First, he stayed tooooo long. Second, he didn’t have the toughness and edginess needed for a Bond. He seemed to want to make Bond into a lighthearted romp.